1619 in Global Perspective

and why we need to study the history of slavery and the African diaspora globally

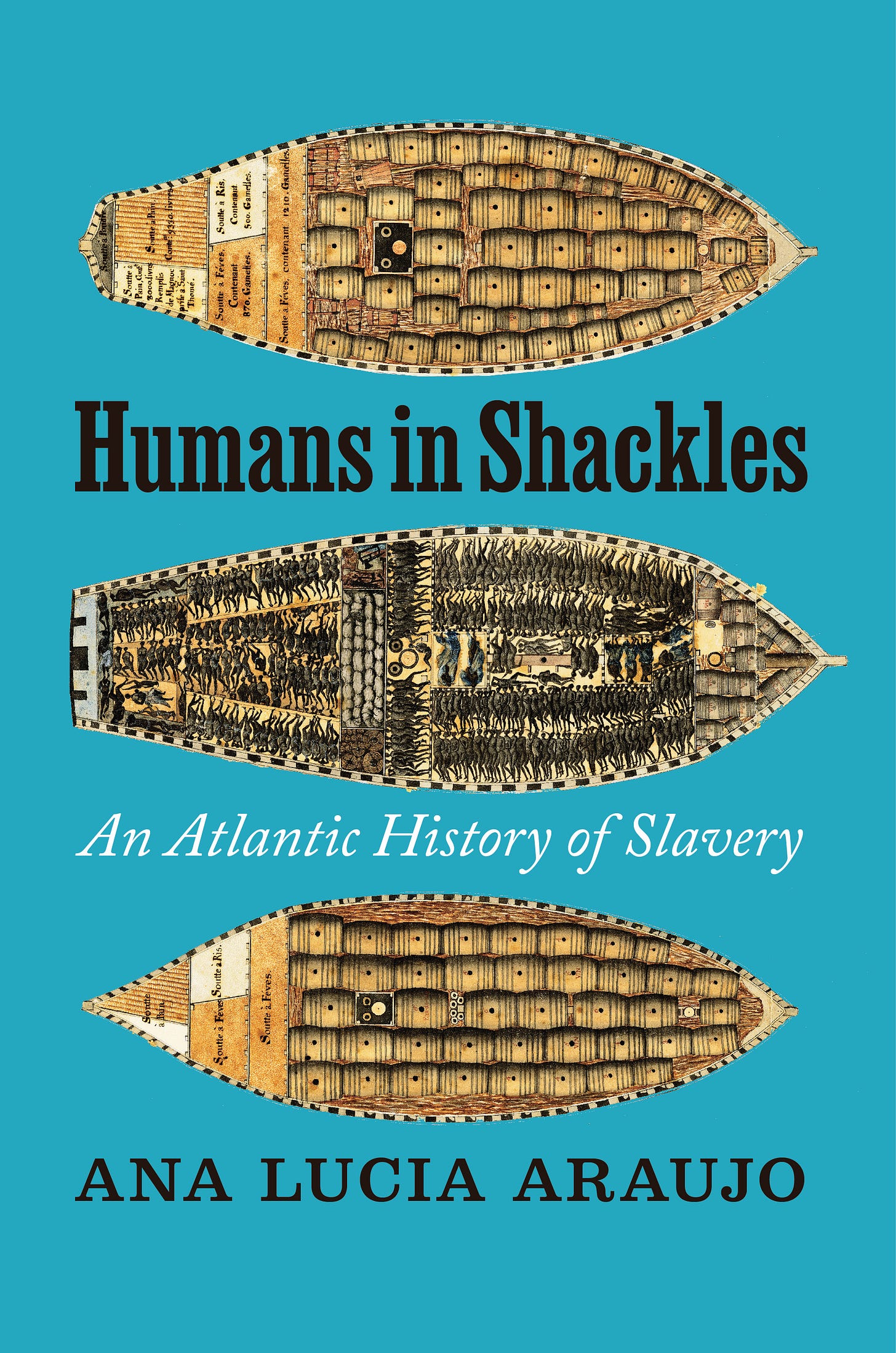

A few days ago, I read a nice piece on Foreign Policy in Focus that mentioned my new book Humans in Shackles: An Atlantic History of Slavery. The piece called for understanding racism and white supremacy beyond the narrow framework of the United States.

As I was writing another article about my book, I decided to share here a revised (and now updated) version of my intervention at a panel on global understandings of the year 1619, which I presented five years ago, at the biannual conference of the Association for the Study of the Worldwide African Diaspora held in Williamsburg, Virginia, in November 2019, a few months before the beginning of the COVID-19 global pandemic. Many elements of what was in play in public debates in 2019 continued to evolve in the 2020 and 2024 presidential elections. But in 2025, these debates show how the rampant divisions visible in those years to some extent contributed to our disturbing present-day context in which the study of slavery and the history of African diaspora is explicitly under attack.

Over the past decades, historical narratives have established 1619 as an emblematic year for the history of slavery and the Atlantic slave trade in the United States, as the nearly 20 enslaved Africans arrived in the then colony of Virginia that year.

Five years ago, as the four hundredth anniversary of this date approached, different social actors and groups, including some historians but especially journalists and public commentators, have embraced this date as a central landmark.

They did so not because of its historical significance or what that year meant to Virginia, the Americas, the Atlantic World, and the African diaspora at the time, but rather to re-signify that event in light of the present's needs.

1619 became a site of memory, a lieu de mémoire, in the sense established by historian Pierre Nora.

In other words, 1619 became a landmark commemorating the Atlantic slave trade and slavery and their deep legacies in the United States. Outside the United States, the significance of the year 1619 is an interrogation mark.

Until recent years historians have referred to 1619 as the year when 20 Africans arrived at Mount Pleasant (Hampton, Virginia). Indeed, several books refer to “20. and odd Negroes” having arrived in Jamestown. Until the 1990s, historians did not know much about these men and women.

For example, in 1992, Howard University historian Joseph Harris, the founding father of the field of African diaspora, in a chapter titled “The African Diaspora in the Old and the New Worlds” published in one of the volumes of the UNESCO General History of Africa referred to these Africans as being indentured servants. Because from the legal point of view, the institution of slavery was only introduced in the English colony in 1661, through the Barbados Slave Code “An Act for Better Ordering and Governing of Negroes.”

In 2019, on the eve of the four hundredth anniversary of 1619, esteemed historian Nell Painter also made a similar argument in an op-ed published in the newspaper The Guardian by stating that the Africans who arrived in Virginia in 1619 were indentured servants.

Yet, as we will see, this designation is inaccurate. As early as 1997 and 1998, other historians such as Engel Sluiter and John Thornton published articles in the journal William and Mary Quarterly that shed new light on the slave voyage that brought “20 Africans” to Virginia, which today is listed with the ID number 107967 in the Intra-American Slave Trade Database section of the SlaveVoyages Database.

In Central Africans, Atlantic Creoles, and the Foundation of the Americas, 1585–1660, historians Linda M. Heywood and John K. Thornton have shed more light on this first documented arrival of enslaved Africans in Virginia. Likewise, in his book Slaves and Englishmen: Human Bondage in the Early Modern Atlantic World, historian Michael Guasco showed how slavery was not a sudden invention by the English in 1619 and that the English knew Atlantic slavery for very long in the Atlantic world.

If chattel slavery did not legally exist in Virginia in 1619, it existed for more than one century in the Atlantic world, including the Atlantic islands along the African coast occupied and colonized by the Portuguese. It also existed in the Iberian Peninsula, and the Americas, including Brazil, the Caribbean, and parts of South America, including present-day Mexico.

In 1619, the Atlantic slave trade had been in progress for more than one century.

In 1619, the Portuguese slave ship São João Bautista was heading to the port of Veracruz, in present-day Mexico. By that time, the Portuguese hold the asiento, the contract to trade in enslaved Africans to the Spanish Americas.

The ship São João Bautista whose captain was Manuel Mendes da Cunha left Luanda in the Portuguese colony of Angola in West Central Africa carrying nearly 350 enslaved Africans, most of whom we believe were enslaved in the Kingdom of Ndongo, located in the region of present-day Angola, and were very probably Kimbundu speakers.

During the Middle Passage, the São João Bautista was attacked by two English ships, the Treasurer and the White Lion that sailed off from the Netherlands, seizing part of the Portuguese slave ship’s enslaved Africans. Eventually, the São João Bautista arrived in Vera Cruz transporting only part of the original human cargo, as indicated on the SlaveVoyages Database, voyage ID 29251.

Now let’s recapitulate some points:

1) Before 1619, according to a Census taken just a few months before August 1619, when the twenty enslaved Africans arrived in Virginia, there were other Africans in the colony, though we do not have records of their arrival.

2) These 20 enslaved Africans were also not the first ones to arrive in the present-day region of the United States. In 1526, enslaved Africans participated in a Spanish expedition to establish an outpost (San Miguel de Guadalupe) on the North American coast in present-day South Carolina. Those Africans organized a rebellion in November of 1526, and destroyed the Spanish settlers’ ability to sustain the settlement, which they abandoned a year later.

3) Also, when Sir Francis Drake arrived at Roanoke Island, North Carolina, in 1586, he brought on board his fleet Africans seized from the Spanish colonies in the Caribbean.

4) Likewise, as early as May 1616, enslaved Africans worked in the British colony of Bermuda on the cultivation of tobacco.

5) Finally, needless to mention that enslaved, freed, or free Africans were present in the region of what became the United States. Among them was Juan Garrido (check the works of Matthew Restall and Hermann Bennett) an African-born man who assisted the Spanish in the conquest of the present-day region of the Caribbean, Mexico, and Florida.

The significance of 1619 is shaped by memory, not by history.

When I say memory, I am not referring to fiction. I am referring to memory as a mode of discourse that while engaging the past is greatly shaped by the present.

We need dates as landmarks to develop commemoration. And in 2025, we need more than ever to collectively remember slavery in the United States, a country still marked by persisting racism, racial inequalities, and white supremacy, and where Black men, women, and children continue to be disproportionally victims of police violence, and mass incarceration.

Yet, these realities also affect other Black populations of the African diaspora, some of them perhaps even to a greater extent. I think here, especially about Brazil, but also about Colombia, Cuba, Peru, and Jamaica. And I also think about Black populations in the African continent.

Then despite the commemorative dimension of 1619, I call us to be cautious with the excessive focus on this US-centered, national framework, that emerges along with the rise of nativist discourses, and the growing insistence (especially in social media) in establishing distinctions (instead of commonalities) between African Americans, Afro-Latinos and Blacks from the Caribbean and African-born individuals. Because such views contribute to reinforcing white supremacy, a system that takes shape with its transnational tentacles. And these are the reasons why, although embracing 1619 as a lieu de mémoire, we should also keep deconstructing it.

And if you want to know more about the transatlantic slave trade and slavery in the Americas before 1619, including Brazil, check my book Humans in Shackles: An Atlantic History of Slavery (University of Chicago Press, 2024).

I very much agree with what you say here. In my own work, I tend to emphasize the papal bulls Dum Diversas, of 1452, and Romanus Pontifex, of 1455, in which Pope Nicholas V somehow presumed to authorize King Alfonso V of Portugal and his descendants to “search out” and “enslave in perpetuity” all “Saracens,” “pagans,” and “other enemies of Christ wheresoever placed.”