How should pre-colonial Africa be curated in the museum context?

Reshaping the Liverpool's International Slavery Museum

The International Slavery Museum, located in Liverpool, United Kingdom, opened in 2007 but has been closed since January 2025 for a major redevelopment.

In December 2024, Adiva Lawrence (Curator at the International Slavery Museum, Liverpool) and Nasra Elliott (Community Engagement Manager of the National Museums Liverpool) invited me to the Reframing African Collections Symposium intended to discuss how the African collections should be presented in the International Slavery Museum, in Liverpool, United Kingdom.

For my intervention at the symposium on February 19, 2025, I was asked to respond to the question How should pre-colonial Africa be curated in the museum context?

There are obviously many answers to this question, depending on the museum and depending on who is invited to answer the question.

In my answer to the invitation, I accepted to explore the topic "Africa" and "Africans" in the Bight of Benin in West Africa—a region that I have studied over the past twenty years—and the Loango coast in West Central Africa—a region that I started exploring six years ago and that was the object of my recent book The Gift: How Objects o Prestige Shaped the Atlantic Slave Trade and Colonialism (Cambridge University Press, 2024).

By looking at these two regions, my aim was to address the challenges of explaining the history of the Atlantic slave trade in these regions by taking into account the diversity of African social actors involved in this inhuman trade and how the museum can avoid the trap of simplifying these interactions as a simple interplay of victims and perpetrators.

But as far as the International Slavery Museum is concerned, I found it hard to address this topic in such a detached manner.

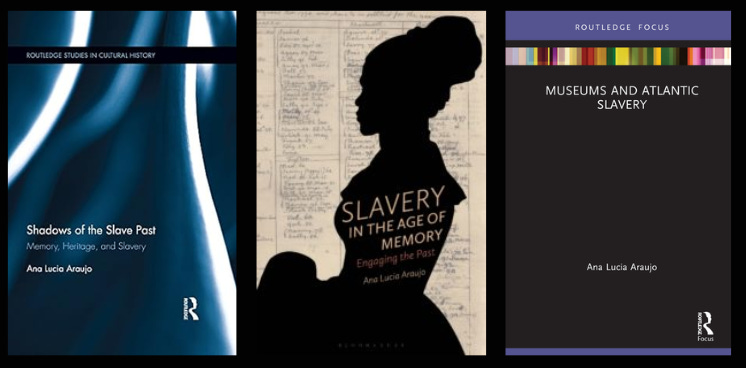

The International Slavery Museum is the first museum of this kind, I visited it several times, over the past fifteen years, and I wrote about it in my Shadows of the Slave Past : Memory, Heritage, and Slavery (2014), Slavery in the Age of Memory: Engaging the Past (2020), and Museums and Atlantic Slavery.

So I prepared my presentation to envision the new exhibition displays unveiled with this sense of loss.

As a historian of the Atlantic slave trade and the African diaspora that I am, and one who studied how these atrocities have been memorialized, the displays of the International Slavery Museum themselves have also been the focus of my work. Although now gone, the displays still tell us the story of how the African past and the Atlantic slave trade were represented in British museums over the past years.

I also have a hard time imagining the future of the International Slavery Museum’s exhibitions as there were several positive outcomes in what was done in the museum in the past two decades. We can go as far as to say that many positive and less positive elements of the old exhibition were reproduced elsewhere in Britain, such as in the Museum of London Docklands’s exhibition London, Sugar, and Slavery, in the French Musée d’Acquitaine in Bordeaux, and even in the celebrated National Museum of African History and Culture in Washington DC.

Drawing on what was done before at the International Slavery Museum, my goal is to discuss what can be done in the new displays to tell the African past, even though I insist that in the context of a British museum, any attempt to tell this history will always be incomplete.

Curating the history of pre-colonial Africa requires addressing a number of questions, and here I will raise two main ones.

First, how the museum can engage pre-colonial Africa as it relates to the nation and the city (Liverpool the British largest slave-trading port)

In Liverpool as in any other city having participated in the Atlantic trade in African persons and the trade of many commodities during the European colonial rule in Africa, telling the history of precolonial Africa requires a dialogue with the city’s communities of African descent, which includes descendants of enslaved Africans who have lived in Britain for several centuries, as well as the descendants of African men and women whose societies were colonized by Britain starting in the late nineteenth century.

The rise of the Transatlantic Slavery Gallery opened at the Merseyside Maritime Museum in 1994 already emerged as the result of these battles for the public memory of slavery. The opening of the International Slavery Museum in 2007 also resulted from those debates, even if its creation was largely shaped by the the bicentennial of the British abolition of the slave trade. In both cases, members of the Liverpool Black communities contributed to the conception of the museum’s displays.

Among others, the now old exhibition included a small display bringing to light how the Atlantic slave trade and Africa were (and still are) present across the city’s through the names of its streets

Yet, as I wrote elsewhere, the representations of Africa in the old museum were still very British-centered, through an excessive focus on West Africa, a region where the British had an important presence during the period of the Atlantic slave trade. By doing so, the museum failed to explain the processes of enslavement in West Central Africa, the most important slave-exporting region, dominated by Luso-Brazilian slave merchants.

A second question to be addressed is how the museum can approach the African past within the limits of its African collections.

But when I say limits, I am referring to the framework of these collections acquired towards the end of the era of the Atlantic slave trade and the rise of European colonialism in Africa. In the case of the International Slavery Museum, most objects are loaned from the World Museum Liverpool’s World Cultures collections, whose African collections include more than 10,000 objects.

As historians we make arguments drawing on the available evidence about the African past in Africa and in the Americas.

Yet, the museum displays are not the pages of an academic monograph, even though if curators have been often tempted to tell everything in a single exhibition and sometimes even in a single display.

As historians, we also make the same mistake. But both the exhibition and the book that try to tell everything are doomed to fail.

The previous displays of the International Slavery Museum mixed objects and artworks from various regions and times.

Sometimes these objects were misidentified with the goal of showing visitors that Africa was and is a diverse continent, with rich arts and cultures

Yet, no European museum of European cultures would dare to mix together disparate objects from different cultures, regions, and periods in the same display.

As the exhibition moved to Atlantic Africa inviting the visitor to understand the history of the Atlantic slave trade, the old displays probably did a better job by explaining how cowrie shells and glass beads were used as currencies to purchase enslaved people, even though the museum website continued referring to barter.

These pitfalls are not solely the responsibility of curators. Among museums dedicated to the history of slavery, the International Slavery Museum—despite its small size—has likely done the most to highlight Africa’s history.

In the UK and across Europe, the academic study of African arts and material cultures is typically housed within anthropology departments rather than history or art history departments. As a result, African arts are displayed not in European art museums but in anthropology and world culture museums, such as the World Museum in Liverpool.

The old International Slavery Museum made an excellent start, given the constraints of its creation—both as part of the bicentennial of the British slave trade and within the limited space available..

As a historian who has studied museum exhibitions and whose work explores material culture, I see two dimensions through which the new International Slavery Museum can tell the history of precolonial Africa. Both dimensions consider the museum’s location in Liverpool—formerly the largest British slave-trading port, with ties to Africa that continued after the end of the Atlantic slave trade and into the colonial era—and the fact that its museums still house thousands of African objects.

The first one is through the study of material culture. The museum can draw on what worked in the previous displays and take much more advantage from the work of historians such as Toby Green to explain how currencies such as cowrie shells, copper manillas, glass beads, and textiles were used in pre-colonial Africa before and after the arrival of European traders in the late fifteenth century. The works Herman Bennett, Kwasi Konadu, Mariana Candido, and Roquinaldo Ferreira can also contribute to decenter the British slave trade, to engage the Luso-Brazilian slave trade.

Centering on the history of fewer single objects, as I did in my own book The Gift can also allow us to tell a fuller history of Africa, Africans, and the various individuals involved in the Atlantic slave trade.

The collections of the World Museum, like those of the British Museum, have many objects asking us to tell their stories, in order to understand by whom, when, and where they were created, what were their uses, and what were their symbolic meanings for the African communities they belonged to. These objects also allow to connect the rise of the Atlantic slave trade and the history of European colonialism in Africa. They also beautifully illustrate the rich history of pre-colonial West Africa and its connections to other parts of the world.

Beyond museum collections, the links between the trade in enslaved Africans and the history of European colonialism are everywhere in Liverpool from the Town Hall to the Martins Bank Building, which is why the history of pre-colonial Africa that the International Slavery Museum intends to tell should not remain confined to the museum’s walls.

Connecting the collections of the World Museum Liverpool and the International Slavery Museum to these tangible traces is also a powerful way to acknowledge how Africa and Africans built Britain during the era of the Atlantic slave trade and British colonialism.

The funding for the redevelopment project of the International Slavery Museum was confirmed on February 19, 2025. The museum is expected to reopen in 2028.