Story

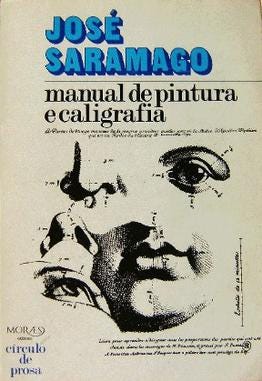

Nearly thirty years ago, I decided to dedicate most of my time to writing with words. Until then, I thought I could write using brushes and pencils and colors and lines. I remember how in those days the words of José Saramago in his novel Manual de pintura e caligrafia (Manual of Painting and Calligraphy) deeply touched me, almost as an epiphany:

Observo-me a escrever como nunca me observei a pintar, e descubro o que há de fascinante neste acto: na pintura, vem sempre o momento em que o quadro não suporta nem mais uma pincelada (mau ou bom, ela irá torná-lo pior), ao passo que estas linhas podem prolongar-se infinitamente, alinhando parcelas de uma soma que nunca será começada, mas que é, nesse alinhamento, já trabalho perfeito, já obra definitiva porque conhecida. É sobretudo a ideia do prolongamento infinito que me fascina. Poderei escrever sempre, até ao fim da vida, ao passo que os quadros, fechados em si mesmos, repelem, são eles próprios isolados na sua pele, autoritários, e, também eles, insolentes.

In English, this could be translated as “I observe myself writing as I never observed myself painting …I will always be able to write, until the end of life, whereas with paintings, closed in themselves, repel, they are themselves isolated in their skin, authoritarian, and also, they are, insolent.

What I didn’t know back then was that writing would become a difficult, a challenging task, as unlike Saramago I would not be able, or even want to write in my first language, Portuguese. It happened slowly. In less than five years, I moved to another country and embarked on a new adventure in which all my academic work was to be written in French. The language I spoke at home and my language of love also became French, or at least as still today a mixture of French and Portuguese. In the first years of this self-imposed exile I wrote blogs in Portuguese. Slowly, I abandoned Portuguese as my writing language.

But writing in French was never easy. French was too close to Portuguese, and it was never fluid. Tant mieux, as I moved again a few years later, my writing language became English. And for more than fifteen years, English it has been.

Histories

Through these multiple moves and changes of language, I became a historian. But visual artists continued to pull me. In Brazil, when I still wanted to be a painter, I got a BA in visual arts, then got an MA in history but with a thesis that examined visual arts, all this in Portuguese. Then I got a PhD dissertation in art history, with a dissertation written in French, and then a PhD in history, with a dissertation also written in French. When I moved to the United States, where I made my career, I embraced English as my writing language, and never looked back. Of course I still write in French and speak French at home. I also write and speak in Portuguese with friends, and I even dare to think that only these friends with whom I can also exchange words in these two languages (the native Portuguese and French, the acquired language of the heart) are those who can better understand who I am.

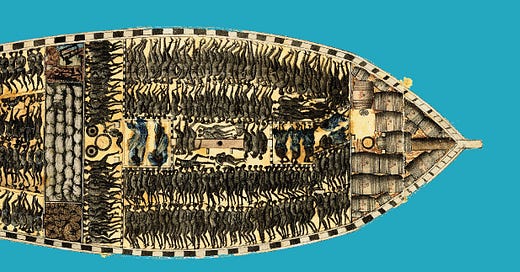

All this rambling about writing and languages is to say that I wrote a large body of academic work (single authored books, edited books, articles in academic journals, chapters in edited books) but I have been trying to build bridges between this academic work and the general public interested in history, and history of human atrocities, and histories of slavery and the Atlantic slave trade that became central to my research and writing.

A few months ago, I published a book Humas in Shackles: An Atlantic History of Slavery.

This was my first book intended for general readers, even though my book Reparations for Slavery and the Slave Trade: A Transnational and Comparative History also reached readers beyond academic circles.

I have been using social media for more than a decade, and in the past years most of my activity on social media has been around making the history of slavery and the Atlantic slave trade visible through the use of the hashtag #slaveryarchive.

But social media is changing. I want to write more and better. And sometimes I want to write longer stories, as disconnected as they can be.

And then I have been reading posts and newsletters by historians who use Substack, and you will see that I recommend some of them, even those whose political positions do not align with mine, and it’s fine because I still like their writing.

Substack X also allows longer posts that land directly in people’s mailbox, like writing vessels.

So, there is something more intimate, or at least something that gives the illusion of more intimacy that social media algorithms do not allow any more.

Which stories

I will be writing here about my work as a historian of slavery, the Atlantic slave trade, and global Africas and its diasporas. Longer posts, shorter notes, on my writing, on sources I have found, exhibitions I visited, books I want to recommend, talks and events I am attending.

You can expect longer posts twice a month. And surprise updates, meanwhile.

All content is free by now, and there will be always free content if one day I add the paid subscription.